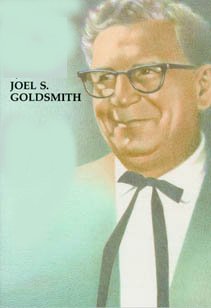

And for me it is my posts about Joel Goldsmith.

There are obviously many dedicated readers and students of Goldsmith's work out there.

One of the comments I got on the blog yesterday prompted me to do this post, as it addressed a question I have myself been considering for many years: Can Joel Goldsmith be called a Christian?

Rhoberta, the commenter, mentioned that Goldsmith himself rejected the label. This doesn't surprise me, as almost all of the New Thought teachers saw themselves as universalists who drew on all the world's religious traditions and whose teachings were in turn accessible across the board. And while this sentiment was admirable, in practise the written work and the rhetoric of Goldsmith, Fillmore and others was so rooted in Christianity and in Biblical reflection that it makes their work very difficult for the non-Christian to negotiate.

I worked for many years in a New Age bookshop, and Goldsmith was always shelved there in the "Christianity" section. I had not read him at this stage, but was fascinated by his books because they were among the only ones that ever sold from that section. I remember asking customers on several occasions what Goldsmith was all about and they suddenly grew very mysterious, and so I was left none the wiser. I read at some stage a passing reference to him in another book as a "Christian Sience writer" and this made him even more mysterious, as Christian Science was by that stage (in mid-90s Australia) an almost entirely forgotten tradition, and I was intrigued as to why we sold so many copies of The Infinite Way.

I'd actually be really interested to see some specific references to Goldsmith's denial of his Christianity, as I have been unable to find any in the books in my collection. I would suggest that his teaching is entirely grounded in the Christian tradition, via the heterodox theology of Mary Baker Eddy. Like his predecessor Charles Fillmore (who had also emerged out of Christian Science), he invoked the Christ ideal in his writing. Australian journalist Tess Van Sommers, in her quaint 1966 overview of Religions in Australia, sums up this theology perfectly, writing "Jesus Christ is not regarded...as a Divine personage. He is looked on as the man who developed the power of divinity within himself to the fullest possible extent. Christ is regarded as the power of God within Jesus, and potentially within all humans, which can enable them to demonstrate their oneness with God."

Goldsmith writes frequently about this idea of an inner Christ, of "the Christ in each one" (Gift of Love, 1975). While it is far from orthodox Christian theology, it is nonetheless an idea entirely focused on the Christian ideal, employing Christian language, and it is rarely expressed in any other way (unlike, for example, in the work of Ernest Holmes, which occasionally makes reference to Buddha-nature and other Eastern spiritual concepts).

Goldsmith describes Christ, or the Christ-ideal, as the ultimate in spiritual attainment, the summit of spiritual perfection, writing in Practising the Presence:

"I was led ultimately to that grandest experience of all, in which the great Master, Christ Jesus, reveals that if we abide in the Word and let the Word abide in us, we shall bear fruit richly..."

Finally, I wanted to make the point firmly that Goldsmith was for many years a conventional Christian Science practitioner, as described so interestingly by Lorraine Sinkler in The Spiritual Journey of Joel Goldsmith, Modern Mystic. One of my other readers, Jean F., rightly castigated me for previously dismissing Goldsmith's Christian Science period as a brief blip in his spiritual development.

So yes, I would suggest that, in all outward forms and for all basic purposes, Goldsmith was a Christian. Certainly, if you pressed one of his books into the hands of an average 21st century secular reader they would be incapable of distinguishing his writing from that of the devotional tracts of more conventional Protestant clergymen - which is why you will normally find his books mouldering away in the "Christianity" section of second-hand bookstores. But I absolutely accept that, on a a more careful analysis, he was a deeply heterodox religious thinker who, perhaps, saw himself as a universalist and whose personal theology was so removed from conventional Christian thinking as to be rejected by most mainstream-Christians as entirely heretical and outside the fold.